Delete My Semantic Scholar Author Profile

In my five years of sporadic checking, Semantic Scholar has never accurately reflected my publication record.

Early on, it included articles from other Nick Walkers. This kind of thing happens. Like Google Scholar and other large scale indices, Semantic Scholar collects and munges data of various quality, and essentially has to guess how many Nick Walkers there are and how to assign papers to them. While you can tell that a paper about service robots is unlikely to come from a synthetic aperture radar expert, or a British professor of chemistry, the technology of 2019 was not up to the task. After failing to correct the issue myself with their limited tools, I eventually emailed support, and they fixed enough of the problem for me to stop trying.

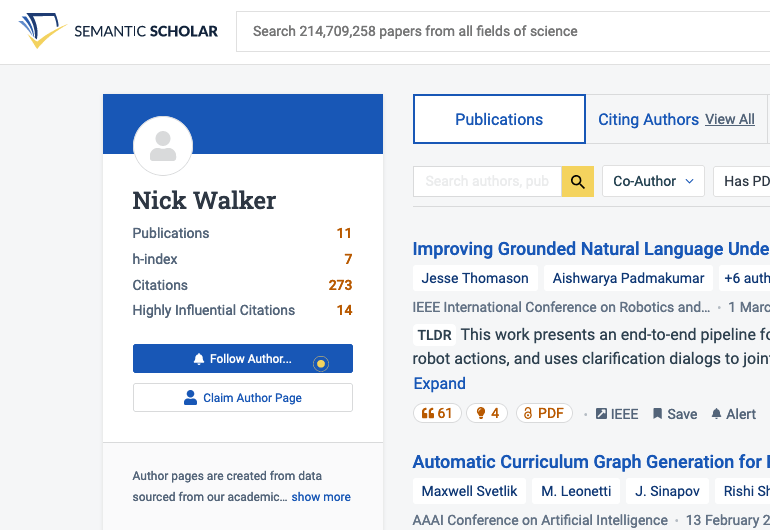

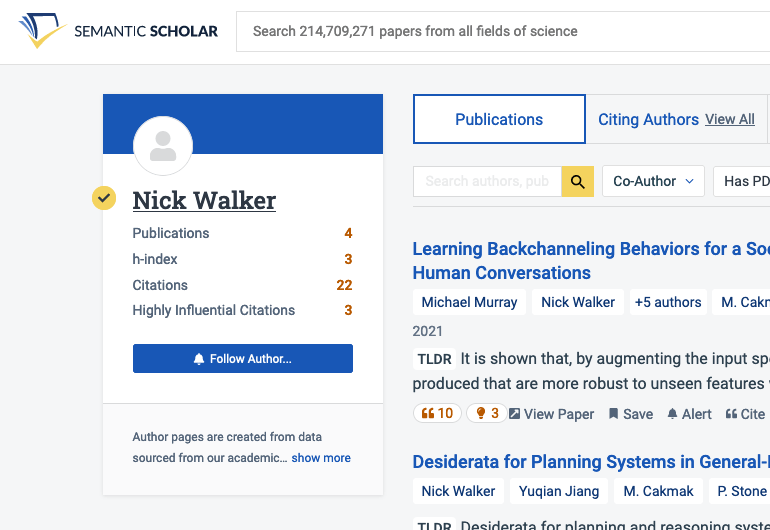

The latest issue is more pernicious. In recent years I’ve had two profiles, a “verified” one which includes four publications, and another which includes the rest. This abbreviated profile is attached to the papers that show up first in most search results for my name. It’s likely that its verification is somehow a result of my flailing to fix the previous issues.

My emails to support over the past couple months haven’t led to the issue being fixed, and there is no other means of recourse. What happens when you send the email? I’m not sure, but based on my observation, support staff approve the request, then file a polite suggestion to some machine learning pipeline which proceeds to do jack all with it.

Update December 20th, 2023: The two profiles have been merged, likely as a result of internal escalation after emailing this post to the team. There remains no way to opt out of having a profile.

Update February 10th, 2025: At my request, Semantic Scholar deleted my profiles. Now there’s a new stub profile (image for posterity), again with the latest crop of papers. Seven years later, still mopping AI slop.

This harm1 is small but familiar. A technology enables something new, something which would’ve traditionally required unimaginable human effort. The technology is pushed to its limit so it can create value. It’s only after this point—due to a lack of earlier critical evaluation2—that a litany of issues arises, issues which can only reliably be resolved with…an unimaginable amount of human effort. As Google Scholar has demonstrated, it’s simpler to create profile pages only for users who want them, as they can then be asked to help fix mistakes. But the resulting sparse graph of author profiles would make Semantic Scholar a much less valuable tool.

Any AI system empowered to publicly characterize a person must allow that person to opt out3. On every author profile, there should be a button to request the deletion of the page, something more prominent than a pointer to the legal team’s email address. I think everyone agrees that the ability to incorporate feedback is a basic4 and necessary feature for a product like Semantic Scholar. But the bar should be the ability to guarantee you won’t have to give feedback again.

-

The harm of generated profile pages should be small, because no important decisions are made based on metrics like citations or h-index (right?). But beyond this, Semantic Scholar’s APIs are broadly available, and might be used in any number of public or private tools. For instance, AI2 has made efforts to facilitate the use of its data in conference paper-matching systems. ↩

-

AI2 have been aware of quality issues with the platform for years. Noah Smith, who works on other projects at AI2, responding to another dissatisfied user four years ago:

I’m not sure where you think this responsibility for “quality control” comes from. Any system this large will involve automation. Anyone who understands automation understands there will be mistakes and improving quality is a continuous process. Don’t like it? Don’t use it.

In a recent email, Noah clarified that it was specifically the expectation of manually checking all results that he felt was unrealistic. He further highlighted the platform’s “[transparency] about the underlying data” and responsive moderation teams as mitigating factors. I am not able to identify from where in the underlying data my duplicate identies are coming from. ↩

-

See the White House’s “Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights” for a more expansive expression of the same view, or the CCPA for a state’s implementation. ↩

-

dblp disambiguated my profile in 2019 within a day of my asking. There haven’t been any mistakes since, perhaps because they defer to standard ORCID identifiers wherever possible. ↩